The Advisor and the Advised: What Does the Future Hold?

Executive Perspectives

I was talking recently to a Fortune 100 CEO whom I and many others consider to be one of the leading business thinkers out there. He told me something that really made me sit up in my chair. He said, “Going forward, pretty much every CEO who wants to succeed is going to have to be prepared to revisit their business plan every three months and start all over again if necessary. The world is changing so quickly right now that unless you understand the speed of that change you have little chance of being able to compete.

Every three months? For a moment I thought I’d misheard him, but it turns out I hadn’t.

When I thought about it more deeply, however, I realized he was probably right. If so, the implications are profound.

More interesting to me, however, is the fact that while most business leaders are talking about the speed with which things are happening all around them right now, from companies disappearing overnight to technologies changing our lives in the blink of an eye, many are not focusing with the same degree of urgency on what they are going to do about it.

It’s almost as if the world has been temporarily forced into a state of rigor mortis while it comes to terms with all that is now happening in this post-COVID, high inflation, recession-like environment with technology like ChatGPT and social media further integrating our digital, physical and social realms.

What does the new normal look like? Is it even normal? Are there questions that we don’t even know the answers to yet because we don’t know the questions? Are we as business leaders and advisors even trained or equipped to deal with all that’s being thrown at us right now? Will it turn out that only the handful of technology companies who truly are able to take advantage of all this tumult will know how to win and everyone else will come in a distant second?

So many questions and so many unknowns. Not an easy time to be told you have to be prepared to alter your business plan every quarter if necessary. CEOs could be forgiven for pushing the pause button until they have better information, even if that means losing some ground on their competition in the short term.

But more about that in a moment. Allow me a brief tangent…

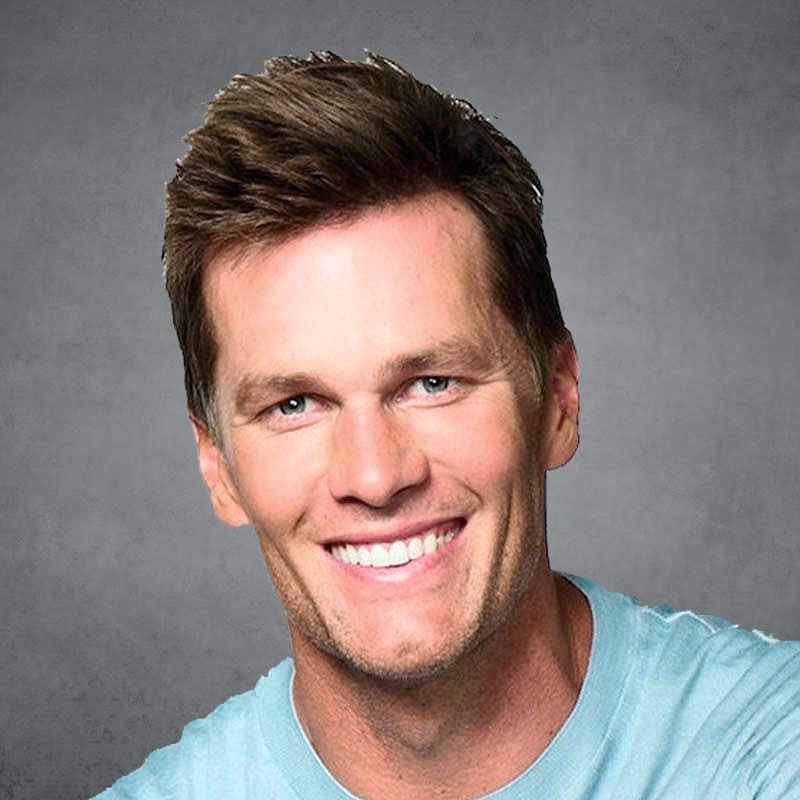

I have always tried to learn from the wisdom of those who have more experience and years under their belt than I do. Now, having arrived at middle age in what seems to my inner self like the snap of my fingers, but in reality, has been a career 30 years in the making, I feel like I am reaping the benefit of that approach when my clients need it most.

- Declan Kelly | Founder, Chairman and CEO

I’m blessed to have been given the opportunity to advise many of the world’s leading CEOs for the last 30 years. It’s a privilege I never take for granted. I’ve worked extremely hard to earn the right to be able to do it and I am always grateful when these amazing leaders are willing to listen when I offer up my point of view.

It comes with great expectations of yourself, however. You need to want to be an athlete in your profession if you want to keep your seat at the table. You need to want to be the best in the world at what you do, or you shouldn’t even try to play. You are only as good as your last piece of advice, you learn to live on your nerves, and if you don’t have an insatiable thirst for knowledge you should choose another profession because there is no hiding place when you are put on the spot and asked what the client should do. This means keeping up to speed with everything that is going on around you – and them – so you can truly add value and not just bloviate on their dime.

We don’t run the companies we advise, but we take it so seriously that we think like we do. Clients can feel it and sense it when you care and if you don’t. They didn’t get to run one of the biggest companies in the world by accident after all. I obsess – literally – about knowing everything I possibly can about the clients I advise. In many cases I have worked with them for multiple years, even decades, and if they don’t win then I take it as personally as they do. There is no other way to do this if you want to do it right.

This is what leads me to spend so many hours a day talking to CEOs who lead the world’s biggest and most important companies. Many are clients, some are not, but I have one rule regardless of my relationship with them: I try to listen a lot more than I speak, so that when I speak, I can show I have listened before I offer any advice.

It sounds simple but you would be amazed by how many times in a meeting most advisors fail to remember who is the client in the room. They fail to realize that they will never know more about the company than the person who has hired them for their advice, no matter how hard they work. Several suck all the oxygen out of the room mostly relying on desktop research for the majority of their opinions, mixed with a dash of prior experience in similar situations. They usually fail to see that the secret to the outcome the client most needs is usually hiding in plain sight inside the company itself.

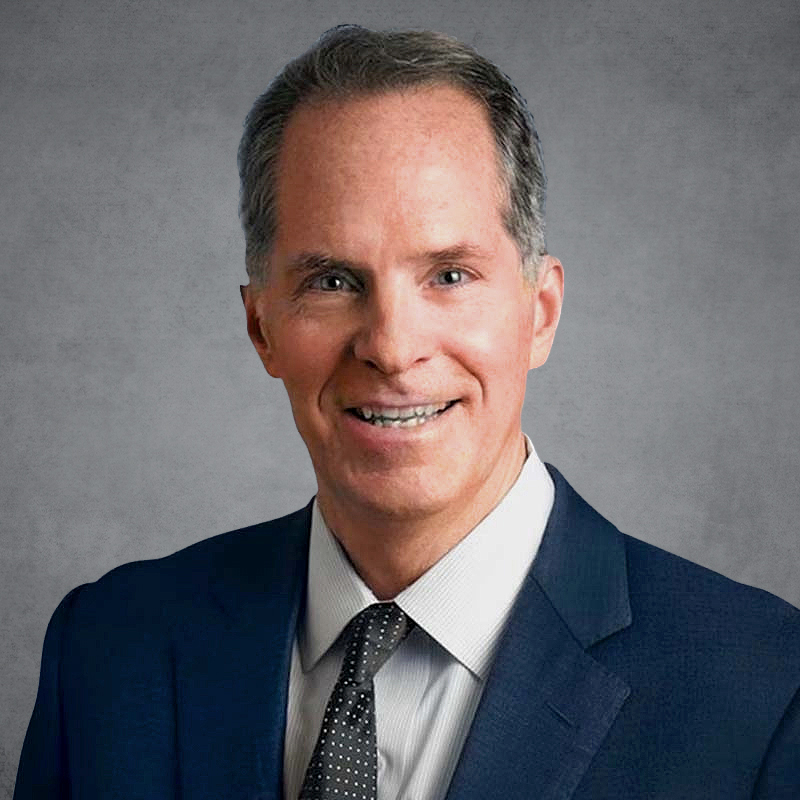

My dear friend and mentor, Marty Lipton, whose place in the pantheon of great advisors was already assured decades ago, is one of the smartest people I know. He had a wonderful answer when I asked him years ago why so many clients wanted to hear what he had to say and how he managed to always sound like the smartest person in the room.

After first challenging my description of him with his usual self-deprecation, he thought for a moment and said, “I guess it’s because I usually make sure to speak last.”

It was, of course, classic Marty. Witty, self-deprecating but also wonderfully simple in its logic. What he was really saying, and I am using my words here, not his, was, “I listen more than I talk. That way I always learn more before I speak.” He has built one of the most admired advisory firms in the world for a reason.

Every coffee or lunch with Marty, or his partner of many decades and another dear friend of mine, Ed Herlihy, is like getting a free lesson from your favorite tutor. If you’re smart you listen hard, take mental notes and resolve to put into practice what you have just heard. Every visit is an opportunity to learn. And both are incredibly generous with their time, so you make a promise to yourself not to waste a second. I’ve never heard two men say so little in meetings but make so much sense while doing it. They don’t feel the need to dominate the conversation because they know that’s not the point of the exercise. They don’t make them like Marty and Ed anymore, and that’s a pity. I’ve been extremely lucky to have had a front row seat on many occasions when they have had something to say in a meeting, and every time it happens, I walk away smarter than when I walked in.

Why is this important and pertinent to the subject of the change that is happening all around us? Because while business leaders are struggling to grapple with what’s going on right now, I sense that most advisors are too. A little knowledge goes a long way. A lot goes even further. I think we are living in an era where, precisely because of the speed of change and the prevailing uncertainties all around us, the best advisors will make a truly critical difference to the companies and CEOs they advise; now perhaps more than ever before in our living memory. That’s why knowledge and adherence to all the attributes I mentioned earlier will become critical determinants in deciding who among us is able to pass that test. It is also one of the primary reasons why we have built Consello the way we did, assembling a team of leaders who truly are among the most accomplished in their fields anywhere in the world. The combined force of all their experience and intellectual capacity will, I believe, distinguish our firm above all others when those moments of criticality arrive for the biggest companies in the world. And we want and expect to be there with and for them when those moments happen.

I have always tried to learn from the wisdom of those who have more experience and years under their belt than I do. Now, having arrived at middle age in what seems to my inner self like the snap of my fingers, but in reality, has been a career 30 years in the making, I feel like I am reaping the benefit of that approach when my clients need it most. Throughout my whole career, in the various firms I have helped build, I have surrounded myself with people who were older and smarter than me. Great people. Hard working people. Honest people. People who would go to the ends of the earth for their clients. They all had one thing in common – a thirst for knowledge. Without that gene you are wasting your time. Literally. You will always learn more from a wise person than one who thinks they’re wise just because they have worked a long time. The two things are not the same. Not by a long shot.

The truly wise ones are those who are resilient enough to be able to stay at the top of their game through multiple different eras and changes in the way the world does business. It will be fascinating to see over the next few years how that evolves as the world hastens its rate of change to levels never previously even imagined.

When I started out as a journalist working for my local weekly newspaper in 1986, I had a manual typewriter and every time I pressed a letter it clunked like a hammer striking an anvil. Then we progressed to the word processor, and I thought my whole world had changed overnight.

I remember covering the Olympic Games in 1992 from Barcelona, having then moved on to working as a reporter for a daily newspaper in Ireland and having to carry around a device called a Tandy in a big briefcase. When filing a story, one had to place two suction cups around the earpiece and mouthpiece of the phone and send the words you’d written back to the news desk via a hard telephone line.

A few years later we moved on to PCs and email and then we really thought we had entered the stratosphere in terms of technology. Oh boy. It could never get better than this. How wrong we were.

Fast forward to today, and in the last few months we have been consumed by the advances in artificial intelligence and its effect on multiple parts of our society, including the written word, and the predictive capacity of technology to make the author/advisor faster, more efficient and more informed within seconds. The thinking will now be done for you most of the time if you want, once the predictive aspect has developed enough to learn how and what you want to think. It took 20 years for my life to change from the manual typewriter to the smartphone and PC. It will, apparently, take no more than three months on an ongoing basis for everything around us to change going forward because of the use of artificial intelligence and other technological advancements.

So what does this mean for CEOs and the companies they run? What does it mean for the advisors who for decades have provided their advice, usually the same way and usually without having to change very much the intellectual tools, models or practices they use to make it happen? Is acquired knowledge with the aid of technology the same as learned knowledge acquired over decades of experience and listening to those who have gone before? Does it matter? Will it matter? Does it only matter if the companies one is advising are moving so quickly that the only way to really keep up with their pace of change is to use predictive technology at the same time? So many unanswered questions. Where do we find the answers?

Which brings me back to my chat with the aforementioned CEO.

I’d never heard his type of thinking before. I’ve been involved in helping write countless strategic business plans for some of the biggest public companies in the world for more years than I care to remember. With few exceptions they all usually have a similar broad structural framework. They all have their long-term goals, usually three to five years, and a short-, medium- and long-term roadmap on how to achieve them. Each year the company’s leadership team meets to measure its performance and track how it’s doing against the plan. Alterations are made based on financial performance and how the company thinks it is doing. Then it uses that measurement to decide how to communicate its progress to investors, employees, partners and other stakeholders. Pretty simple stuff. And it seems to work.

But what if the CEO is right? What if the world around us is changing so much and at such speed that we need to throw the rule book out the window and call everyone back to the office? Do they actually work “in the office” anymore? Is that a good or a bad thing? Will this experiment with hybrid work last? Is it an experiment or is it already part of the social fabric of our lives? Do we want to work like we have up to now? Does predictive technology make it easier for people to work from home such that even fewer people will eventually be needed at the office, or needed, period? Will predictive AI technology be even able to answer all these questions for me so I don’t have to answer them myself? If so, what will I do with my time?

Isn’t this whole thought process exhausting? You bet your life it is. Isn’t that why we need the technology in the first place?!

I find this whole thing fascinating, scary, rejuvenating and exhilarating all at the same time, to be honest. The one thing I do know is that I plan to embrace it rather than to let it embrace me.

Going back to my original thesis around how to do what I and others like me do every day, knowledge is at the core of everything. So, if it does indeed come to pass that companies are going to have to rip up their business plans and start again every three months, then so be it. We will deal with it and adapt. At least some of us will. Others may not.

Perhaps when all is said and done, this whole new social experiment with technology becoming inextricably linked to how we live and work every day may produce a whole new standard of excellence where you either adapt or disappear, just like the companies you are advising. Framed this way it sounds kind of fair, actually. This is likely another time in our history where this thesis is going to be put to the test.

COVID is the most recent test of society’s ability to adapt to the speed of change. And the fact that it happened so quickly should perhaps not really be surprising. Companies, like people, are highly adaptable with the right leadership.

I see examples of it everywhere I go.

I have been to more than a dozen headquarters of major companies around the U.S. in the last six months to meet with CEOs. Their campuses literally looked like ghost towns, with the leadership working in their offices while everyone else worked from home, leaving the CEO to usually confirm to me that they were putting the offices up for sale or lease because nobody was ever coming back. In addition to their long-range plan, many had decided to now work off a rolling three-month plan because supply chains had been decimated, inflationary pressures were worse than anyone could remember for more than two decades, and many of the old rules that governed how performance was forecasted pre-COVID had now been thrown out the window.

So maybe companies are ripping up their business plans every three months anyway, not just because of the implications of technology but because businesses are remaking themselves in real time, and that means doing everything faster, more nimbly and with a lot less advance planning. Maybe technology is meeting a need in society and society is meeting a need in technology all at the same time. Maybe my CEO friend doesn’t sound so extreme after all.

When I was in Davos this year I watched with interest as several CEOs went on television to talk down full-year guidance or the very notion that they could reliably predict what was going to happen in 2023 because things had changed around them so quickly and with such unpredictability. There was lots of talk in the corridors of even giving up the whole idea of providing annual guidance and just telling people every quarter how the company had done in the previous three months and leaving it at that.

I began to think to myself, maybe we should hold that thought. What if annual guidance wasn’t a thing anymore? What if we all moved to just quarterly guidance instead? Or maybe no guidance at all (I hear every CEO applauding as they read this right now), where public companies show up every three months and the numbers will be what they will be?

It certainly would simplify and reduce the impact of a whole industry that has invented itself to feed on the speculation of whether someone meets or beats a notional consensus target of a group of sell side analysts who invariably always work with a lot less information than the companies they are covering.

I’ve helped build two of the largest IR businesses in the world during my career and I’ve never understood why companies haven’t come together to change the ridiculous nature of that quarterly interaction anyway. It makes almost no sense.

Three months means nothing in the life cycle of most companies. Yet every CEO, CFO and their management teams spend countless weeks preparing for calls trying to predict what they will do in the next quarter, when they could be doing something far more productive during that time like making more money for shareholders, creating value for stakeholders and letting the numbers be whatever they will be. After all, if companies should be prepared to reinvent themselves every three months, this exercise of predictive quarterly guidance seems moot. I would not be surprised if at least long-term guidance becomes a thing of the past. I also wouldn’t be unhappy.

So, after all that, as the weeks have passed since I spoke to the aforementioned CEO, I have become more and more convinced by elements of his argument.

Is the speed of competitive change going to drive companies to constantly reinvent themselves at speeds they previously thought unimaginable, whether they like it or not?

Is there a confluence of events happening here where we live our lives this way because technology allows us to and society expects us to, while at the same time technology also innovates companies so rapidly that they must either change or die? Will we soon be able to do all these things through AI such that we won’t even have to think about it anymore and a machine learning robot who teaches itself to express “emotion” can likely make better decisions than we can by analyzing and rationalizing the balance of probabilities?

Will those aforementioned analysts even exist as a trade in five years? After all, can’t a predictive robot predict guidance as well as a human? Can’t they do it in real time instead of waiting several weeks into the quarter for someone to issue a largely opinion-based report? I believe they probably can, in time. I believe the sell side as a “thing” is eventually going away and its time is limited anyway.

Just like many of those who currently work in the proxy industry and chase shareholders for paper ballots to be returned on behalf of companies ahead of the proxy deadline should be looking for a new form of employment soon. Going forward, if an activist wants you to vote in favor of their activist proposal, they are going to be able to email it to you directly and offer you the ability to say yes or no at the push of a button on your phone. These are just examples. There are many more that I am sure are obvious.

All of this brings me full circle to where we started.

If public company CEOs and their advisors are going to have to rewrite or at least review/rethink their business plans every three months, then the consequences of such change will be enormous, but not necessarily all bad.

For those who run those companies maybe it allows them to do so without having to worry about the same things they worry about today and learn to focus on the ever-evolving pace of change affecting their work rather than telling people all the time about the work itself. Knowledge and experience will become more important than ever before in differentiating the advisor in the eyes of the advised. Yet the tools and methods of delivering the knowledge are rapidly changing. Technology, if used properly, can make everyone better and more efficient, and the whole way we assess the performance of advisors and the advised in the relationship can be taken to a whole new level.

As I said, the thing I find most interesting about the pace of change we are experiencing right now is that everyone is talking about it almost in the abstract but very few are talking about what they are going to DO about it or what it is going to do to them. They might want to start thinking more deeply about these questions before it’s too late. To quote the great Irish poet W.B. Yeats in his eternally poignant poem about the Irish revolution, Easter, 1916, “All changed, changed utterly: A terrible beauty is born.” It looks like it’s here to stay. And maybe it’s time for all of us to start getting with the program.

The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent those of The Consello Group. Consello is not responsible for and has not verified for accuracy any of the information contained herein. Any discussion of general market activity, industry or sector trends, or other broad-based economic, market, political or regulatory conditions should not be construed as research or advice and should not be relied upon. In addition, nothing in these materials constitutes a guarantee, projection or prediction of future events or results.