Heads or Tailwinds: Weathering the Current Macro Environment

Executive Perspectives

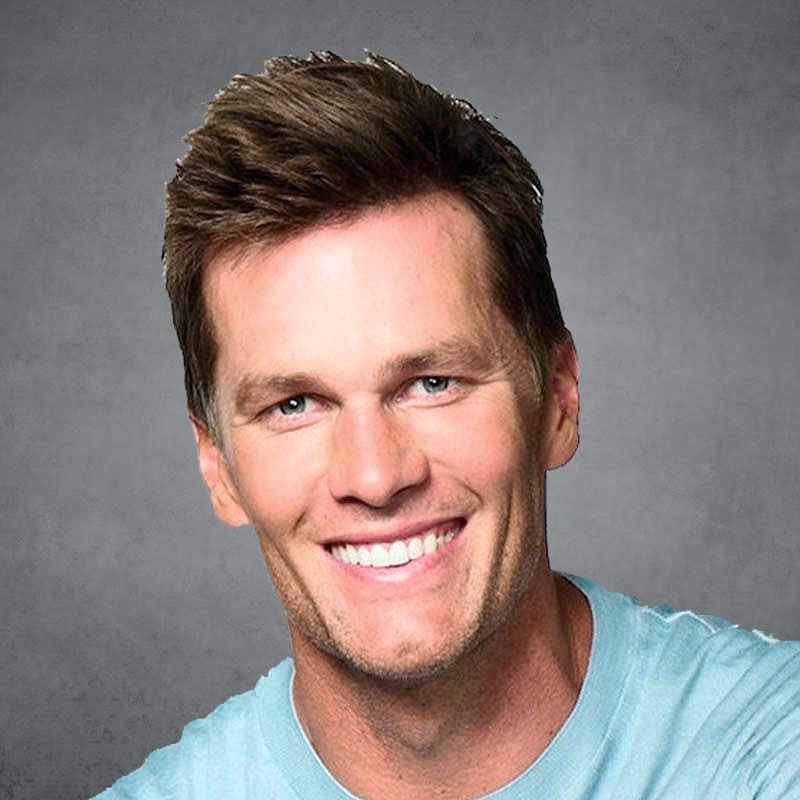

While history doesn’t repeat itself exactly, it does rhyme. I’ve learned that reiterating “this time is different” has never been a money maker for me. Every time I’ve heard that phrase, the past tends to reemerge in some way.

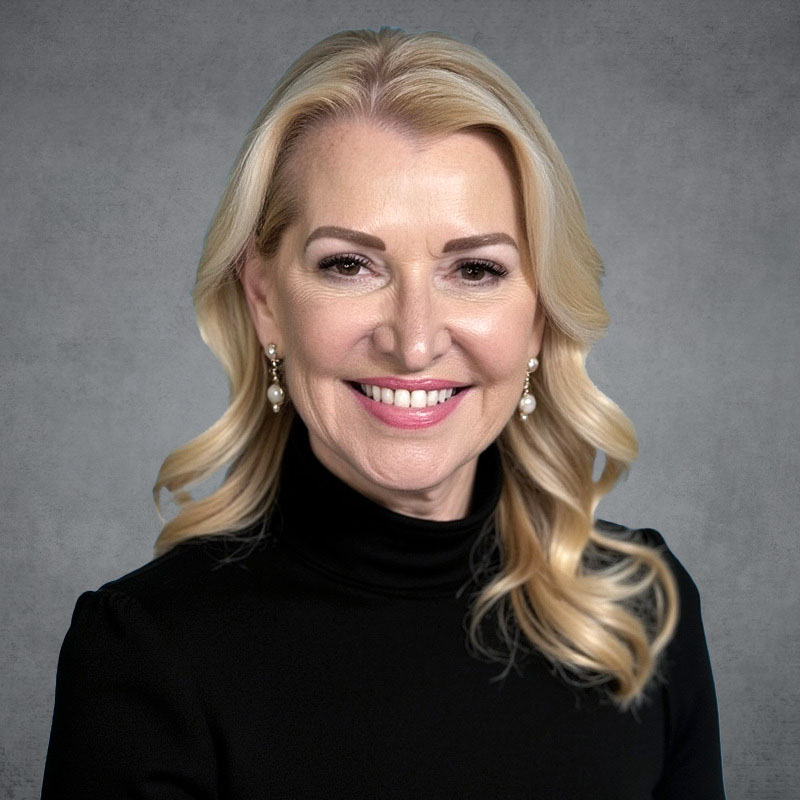

Making predictions is hard, especially (we economists often joke) about the future. But in 2023, we expected cyclical inflation to come down rapidly and it did. We did not expect secular inflation to come down as sharply, and indeed it did not. Consequently, upward pressure on the 10-year Treasury yield continued, with rates beginning the year around 3.9% and peaking last fall at nearly 5% before some relief was granted in the fourth quarter.

Based on these rate shifts, we’ve seen that people are getting a bit too optimistic about where inflation and interest rates will settle out. For example, structural inflation primarily hinges on labor. Commodity prices have come down in the last year, but if labor costs, which tend to be stickier, don’t come down materially, that trend will influence underlying inflation and rates.

These factors, and numerous others, create headwinds and tailwinds that impact where interest rates will land and, as a result, how investment managers choose to manage money. If we evaluate the headwinds and tailwinds we’ve experienced over the past 20-40 years, many tailwinds have driven the global economy upward and created a favorable macro environment for investors. Going forward, some of those existing tailwinds will fade, some will turn into headwinds and we’ll encounter other, new headwinds that will create challenges for money managers.

Using a probabilistic reasoning approach, investing involves forecasting future returns at an appropriate risk discount that considers variability around geopolitical risk, global economic factors and financial markets. As corporations face additional headwinds, at best, the starting point is not particularly advantageous. Going forward, the paths to returns are unlikely to be an improvement over what they have been in recent decades.

Shifting Winds of the Global Economy

The main tailwind we experienced over the last 15-20 years was lower inflation which led to lower interest rates but still allowed for economic growth. Central banks around the world lowered interest rates to near zero after the global financial crisis in 2008, and many kept them there until 2022. Corporate profits rose dramatically on the back of lower interest and tax rates as businesses could obtain cheap financing and increase capital investments. Stock markets soared. Money was readily available. Deals got done more easily with cheap money. The geopolitical environment was often benign and global trade soared.

Now the winds are shifting and inflation, higher interest rates and challenges to economic growth are likely headwinds going forward. Inflation has picked up to higher levels than we have experienced in four decades and is unlikely to drop much from here, particularly due to higher labor costs. This is a new situation for many money managers who do not have the historical experience or perspective to inform decisions. As expected, given this inflationary environment, interest rates have come down from previous peaks and likely will not fall much further. The benefits from lower interest costs that many businesses have experienced – or, worse, relied on – will likely disappear as governments grapple with demographic challenges, investors struggle with expensive money and stock prices, and global economies absorb increasing geopolitical risks.

Declining Profitability, Tempered Growth Expectations

The tailwinds that have fed underlying profitability for many businesses will shift in the next year and beyond. Broadly, earnings growth is less likely to be as robust and valuations placed on those earnings are less likely to be as strong as we saw in the era following the 2008 recession. In other words, we expect an emergent slowdown in corporate profit growth and share price returns.

In a 2023 article from the Federal Reserve Board, the author found that the decline in interest rates and corporate tax rates accounted for the majority of exceptional stock market performance from 1989-2018 – and more than 40% of real growth of corporate profits. These tailwinds were dramatic for businesses over this period: The 10-year Treasury yield had fallen from 6% in 1989 to just 1.9% in December 2019. Similarly, the corporate tax rate dropped precipitously over this period with the effective rate for the S&P 500 falling to 15% in 2019 from 34% in 1989.

Moving forward, we’re unlikely to see a similar boost to profits and valuations from ever-declining interest and corporate tax rates. There is simply not space for interest rates to fall below those previous lows, even if they do slowly come down from their relative peaks. Similarly, the massive debt of the U.S. would indicate fewer opportunities to decrease corporate taxes.

These rate effects will impact investment decisions for money managers because the returns we have seen are unlikely to be repeated. Returns might be 6-7% per year but won’t be double that range as some money managers have been able to achieve. Moreover, against Treasury bill rates in mid-single digits, suddenly these investors have a market where it’s not uncompetitive to invest in risk-free alternatives.

Therefore, growth is slowing down because much of that previous growth was predicated on combined tailwinds of lower taxes and interest rates. Now, at best, those tailwinds might neutralize if interest and corporate tax rates return to their lows. That scenario seems unlikely in the near term, which means those tailwinds will more likely become headwinds.

Geopolitical Tailwinds Likely to Reverse

Globalization has been a sizable tailwind for businesses in the last 50 years. Data from the World Bank shows that world trade as a percentage of GDP was 25% in 1970. By 1990, it had risen to 38%. In 2022, it was 63%.

Currently, factors from supply chain disruptions from pandemics and wars to demographic challenges impacting labor costs to global political uncertainty are all increasing the risk of investment in ways that will often suppress returns and profitability. Thus, the tailwinds from geopolitical factors are easing while the headwinds are strengthening.

Supply Chain Costs

Businesses have benefitted from generally cheap manufacturing from low labor costs in recent decades. That’s because many goods were produced in countries like China, Bangladesh and Vietnam. These sourcing decisions made sense; the more places from which businesses can source things, the more likely they are to get lower prices. Now, a case could be made that this tailwind could be reversed, and businesses not only lose out on diversified sourcing options but are likely to go in reverse because of geopolitical risk.

Those low costs are under threat for a variety of reasons, including nationalistic policies that instill trade barriers domestically. These policies are not all political in nature. The experience of COVID-19, where many businesses did not want to import because of health risks or supply chain disruptions, led to a trend of onshoring or nearshoring. More recently, we’ve seen how geopolitical factors have disrupted supply chains, such as the closing of the Suez Canal in December 2023 or Houthi attacks on ships in the Red Sea in 2024.

The reason many businesses went offshore initially was to get cheaper labor. Assuming there is a certain symmetry in these calculations, when we bring things back onshore, businesses will see higher costs that either get passed on to consumers (higher inflation) or absorbed by the company (lower profit margins).

Demographic Shifts and the China Challenge

While we do not want to overestimate its impact, we cannot underestimate how globalization and the opening of China have lowered costs and increased returns for businesses. However, like many geopolitical factors, China’s impact may become a rising headwind for many businesses. While economists can point to Chinese belligerence and anti-Chinese sentiment leading businesses worldwide to seek other places to produce goods, China’s challenges may prove more systemic.

China has consistently been at the forefront of macroeconomic discussions for a variety of reasons, but one that had become salient to most economists by 2023 was its aging population. While aging is a problem for most developed nations, China’s issue is exacerbated by its one-child policy. The actual population of the country is declining, and the size of the workforce compared to that of the non-workforce is shrinking.

Virtually all of the major economies, except for India and possibly the U.S. depending on where immigration policy lands, will have decreases in the number of working people compared to non-working. These demographic shifts will have major economic impacts; comparing China to India, there will be an increase in people taking income in the form of pensions and other tax-funded support and fewer earning income.

We cannot argue with demographics – we know with relative accuracy what the population of most countries will be decades from now. This sharp falloff in workers versus non-workers will put fiscal pressures and growth constraints on the economy. Not only will there be fewer people to make goods, but there will be more who want to buy them, which will have economic consequences.

Outstanding Geopolitical Questions, Uncertain Risk

If risk can be measured, it becomes important. For example, a recent study from the American Economic Review measured how geopolitical risk has impacted discount rates back to 1985, stating, “high geopolitical risk leads to a decline in real activity, lower stock returns, and movements in capital flows away from emerging economies and towards advanced economies.” In other words, with higher geopolitical risk, this model predicts lower returns.

Businesses that are looking to make investments have to account for these risks to their returns. In the geopolitical sphere, we have known and unknown risk factors. For example, what if China attacks Taiwan? What if war in the Middle East expands? What if shipping closures continue to impact global supply chains? Are U.S. companies prepared with the needed redundancy to continue to operate?

High geopolitical risk leads to a decline in real activity, lower stock returns, and movements in capital flows away from emerging economies and towards advanced economies.

- Jeffrey Weingarten | Former CEO/CIO of Goldman Asset Management

Compared to the last 30 years, we are losing the tailwind from the peace dividend we experienced from the fall of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Berlin Wall and relative political stability in developed nations. There is not much of a peace dividend now. From China building its footprint in Africa to right-wing nationalists gaining authority in Western governments to war risk in the Middle East and Russia, we are seeing simmering geopolitical impacts that cut the tailwinds of globalization and introduce significantly higher risk and lower returns.

Economic Factors: The Headwinds We Are Already Experiencing

Before the pandemic, developed nations had largely experienced low, stable inflation for several decades. Many investors had never seen price fluctuations as volatile as what had occurred in 2021, particularly in asset classes such as fixed income.

However, while real returns primarily come down due to higher discount rates and interest rates, it is unexpected rate increases that have more of an effect on returns than profits in the short run. Looking at the 1970s as an example, there was an extended period where the stock market did not achieve the high peak from 1972-73 for seven years afterward as interest rates increased throughout the decade.

In theory, because investors adjust expected returns by alternatives (i.e., if the risk-free rate is high, they will demand higher returns from riskier assets like the stock market), we’ve had very high returns in investment since the financial crisis because there were no great risk-free alternatives. When short-term interest rates are near 0% and long-term government bonds aren’t yielding all that much more, asset managers must find a way to earn 5-6%. The only viable choice, then, is the stock market. In that macro environment, most investors go into the stock market, the stock market goes up and everyone gets returns. Stock prices go higher because alternative investments are not as great. In the current environment, if investors can get 5% in government bonds or Treasury bills, it makes more sense to sit there. As a result, there is less investment in the stock market where returns are more volatile.

These economic factors have a real impact on businesses when it comes to investment in working capital, with shifts driven both by the interest rate environment and scars from the pandemic. We saw unprecedented responses from governments during the COVID-19 pandemic and corporates that hustled to keep up and experiment with uncommon choices and unanticipated results. When we think about the next catastrophe, we have good examples of what businesses are doing to successfully adapt in this world of a global supply chain and just-in-time inventory. Now, between COVID-19, various geopolitical supply chain disruptors and variable supplies coming from China, businesses can often no longer afford to have just-in-time inventory. They must increase inventory and working capital and install new means of supply chain operations oversight. That’s money businesses have to invest in their own companies. If they need to borrow money to meet these inventory needs, it will cost them even more in this high interest rate environment.

Financial Markets Face a Challenging Backdrop

After rapid interest rate increases in recent years to around 5.25-5.5%, economists know the Fed will act to place a lid on inflation before gradually decreasing interest rates. In fact, that’s what the Fed told us would happen: We know the market was forecasting six interest rate cuts in 2024, but already we have had to temper expectations. To be clear, markets still anticipate cuts, with the Fed Funds Rate expected to hit 4.5% by the end of 2024 and 3.75% by mid-2025.

These expectations are similar to those over the last two years that have not materialized. Probabilistically, how many interest rate cuts can there be? We are unlikely to see six rate cuts through 2024, but expectations around these cuts – like when Jerome Powell makes unexpected announcements that the Fed will not cut rates – have driven the stock market into temporary tailspins.

The stock market itself is experiencing a shift to greater concentration as its performance has largely hinged on a handful of tech stocks. This aggregation is not unlike the Nifty 50 stocks in the 1970s. Now, the Magnificent Seven stocks accounted for roughly 60% of stock market performance in 2023. With a rapid increase in valuations among a small set of tech companies, these increased concentrations are comparable to what we saw in the 1990s tech bubble. Now, just 10 companies account for over 30% of the S&P 500’s value. Such concentration in the S&P 500 is not a great indication of the robustness of the index overall, which makes the stock market an even riskier alternative for investors moving forward.

Finding alternatives to public markets in private investment could offer reasonably good returns, but investors have more of an emphasis on cash flow generation in companies that require large amounts of borrowing. Buying a company, leveraging it and selling it won’t work quite as well as it has in the past.

If you consider the continued impact of high interest rates, capital-intensive companies will struggle as those that have benefited from lower interest rates won’t get the same benefits they have in the past. Similarly, companies that are in the service industry are likely to experience higher labor costs from wage growth, which leaves a smaller set of companies that can take advantage of the current environment.

Flying Into Headwinds

There really is not much that is different about investing in the current macro environment compared to the one we saw just a few years ago. Just as it has always been, expected investment success going forward is measured by expected return, discounted at a determined value.

What has shifted are the factors investors must account for and the options they must consider for generating returns. Riskier alternatives are getting riskier while risk-free alternatives seem more appealing.

The earnings growth many corporations experienced over the last few decades was significantly helped by lower interest expenses and lower taxes. Similarly, lower interest rates probably accounted for the increase in valuations. To expect similar returns going forward, there must be the assumptions of continued declines in inflation and tax expense. Neither the inflation trends nor the fiscal outlook suggests either likelihood.

It is not enough to tell a pension manager to temper their expectations, however, which means money managers need to have a keen sense of the geopolitical, economic and financial market factors that will impact their set of investments in the near- and long-term. Similarly, business leaders must plan for the impacts these factors play in their strategic planning and capital budgeting.

Even as tailwinds slow or become headwinds and businesses and investors must shift their approaches to maintain profitability and returns, there is a rhyme to the macro environment we are seeing today – which means there is a way forward to weathering it successfully.

- 1

Smolyansky, M. End of an era: The coming long-run slowdown in corporate profit growth and stock returns. Federal Reserve Board. (2023 June 26). Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2023041pap.pdf

- 2

Trade (% of GDP). The World Bank. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS

- 3

Li, S. & Qi, L. India’s Population Surpasses China’s, Shifting the World’s ‘Center of Gravity.’ The Wall Street Journal. (2023 April

14). Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-china-population-economy-9dd7bf27 - 4

Caldara, D. & Iacoviello, M. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. Federal Reserve Board. (2018 Feb.). Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/ifdp/files/ifdp1222.pdf

- 5

Mitchell, C. Historical Average Stock Market Returns for S&P 500 (5-year to 150-year averages). TradeThatSwing. (2024 Jan.

8). Retrieved from https://tradethatswing.com/average-historical-stock-market-returns-for-sp-500-5-year-up-to-150-year-averages/ - 6

Ghosh, I & Bhat, P. Fed to cut in Q2, probably June; economists less dovish than markets – Reuters poll. Reuters. (2024

Jan. 23). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/fed-cut-q2-probably-june-economists-less-dovish-than-markets-2024-01-23/ - 7

CME FedWatch Tool. CME Group. (2024 March 4). Retrieved from https://www.cmegroup.com/markets/interest-rates/cme-fedwatch-tool.html

- 8

Pound, J. Fed Chief Jerome Powell says a March rate cut is not likely. CNBC. (2024 Jan. 31). Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2024/01/31/fed-chief-jerome-powell-says-a-march-rate-cut-is-not-likely.html

- 9

Krauskopf, L. ‘Magnificent Seven’ continued market dominance rests on sales growth, Goldman says. Reuters. (2024 Feb. 5).

Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/magnificent-seven-continued-market-dominance-rests-sales-growth-goldman-says-2024-02-05/ - 10

iShares Core S&P 500 ETF. iShares. (2024 March 4). Retrieved from https://www.ishares.com/us/products/239726/ishares-core-sp-500-etf

The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent those of The Consello Group. Consello is not responsible for and has not verified for accuracy any of the information contained herein. Any discussion of general market activity, industry or sector trends, or other broad-based economic, market, political or regulatory conditions should not be construed as research or advice and should not be relied upon. In addition, nothing in these materials constitutes a guarantee, projection or prediction of future events or results.